The Morgenthau Plan and the Problem of Policy Perversion

Prof. Anthony Kubek

Link:

http://www.ihr.org/jhr/v09/v09p287_Kubek.html

The Morgenthau Diaries consist of 900 volumes located at Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York. As a consultant to the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, I was assigned to examine all documents dealing with Germany, particularly ones related to the Morgenthau Plan for the destruction of Germany following the Second World War. The Subcommittee was interested in the role of Dr. Harry Dexter White, the main architect of the Plan.

Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr. served in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Cabinet from January of 1934 to July of 1945. Before Morgenthau was appointed Secretary of the Treasury, he had lived near Roosevelt's home at Hyde Park, N.Y. for two decades and could be counted as one of his closest and most trusted friends. His appointment was clearly the culmination of twenty years of devotion to, and adoration of, his neighbor on the Hudson. According to his official biographer, Morgenthau's "first joy in life was to serve Roosevelt, whom he loved and trusted and admired." /1

The Treasury Department under Secretary Morgenthau had many functions that went beyond anything in the Department's history. The Morgenthau Diaries reveal that the Treasury presumed time and time again to make foreign policy. In his Memoirs Secretary of State Cordell Hull described it in these terms:

Emotionally upset by Hitler's rise and his persecution of the Jews, Morgenthau often sought to induce the President to anticipate the State Department or act contrary to our better judgment We sometimes found him conducting negotiations with foreign governments which were the function of the State Department. His work in drawing up a catastrophic plan for the postwar treatment of Germany and inducing the President to accept it without consultation with the State Department, was an outstanding instance of this interference. /2

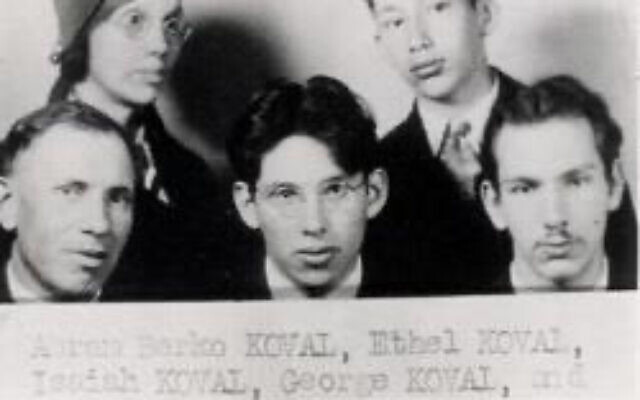

Actually it was Dr. Harry Dexter White, Morgenthau's principal adviser on monetary matters and finally Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, who conducted most of the important business of the Department. The Diaries reveal that White's influence was enormous throughout the years of World War II. Shortly after Morgenthau became Secretary in 1934, White joined his staff as economic analyst on the recommendation of the noted economist, Prof. Jacob Viner of the University of Chicago. Then 42 years old, White was about to receive a doctorate in economics from Harvard University, where he previously had taught as an instructor. He moved up quickly in the Treasury Department, named in 1938 as Director of Monetary Research and in the summer of 1941 acquiring an additional title as "Assistant to the Secretary." Articulate, mustachioed, and nattily dressed, he was a conspicuous figure in the Treasury but remained unknown to the public until 1943, when newspaper articles identified him as the actual architect of Secretary Morgenthau's monetary proposals for the postwar period.

The Diaries reveal White's technique of dominating over general Treasury affairs by submitting his plans and ideas to the Secretary, who frequently carried them directly to the President. It is very significant that Morgenthau had access to the President more readily than any other Cabinet member. He ranked beneath the Secretary of State in the Cabinet, but Hull complained that he often acted as though "clothed with authority" to project himself into the field of foreign affairs. Morgenthau, Hull felt, "did not stop with his work at the Treasury." /3

Over the years White brought into the Treasury a number of economic specialists with whom he worked very closely. White and his colleagues were in a position, therefore, to exercise on American foreign policy influence which the diaries reveal to have been profound and unprecedented. They used their power in various ways to design and promote the so-called Morgenthau Plan for the postwar treatment of Germany. Their actions were not limited to the authority officially delegated to them: their power was inherent in their access to, and influence upon, Secretary Morgenthau and other officials, and in the opportunities they had to present or withhold information on which the policies of their superiors might be based. What makes this a unique chapter in American history is that Dr. White and several of his colleagues, the actual architects of vital national policies during those crucial years, were subsequently identified in Congressional hearings as participants in a network of Communist espionage in the very shadow of the Washington Monument. Two of them worked for the Chinese Communists.

Stated in its simplest terms, the objective of the Morgenthau Plan was to de-industrialize Germany and diminish its people to a pastoral existence once the war was won. If this could be accomplished, the militaristic Germans would never rise again to threaten the peace of the world. This was the justification for all the planning, but another motive lurked behind the obvious one. The hidden motive was unmasked in a syndicated column in the New York Herald Tribune in September 1946, more than a year after the collapse of the Germans. The real goal of the proposed condemnation of "all of Germany to a permanent diet of potatoes" was the communization of the defeated nation. "The best way for the German people to be driven into the arms of the Soviet Union," it was pointed out, "was for the United States to stand forth as the champion of indiscriminate and harsh misery in Germany." /4

Anyone who studies the Morgenthau Diaries can hardly fail to be deeply impressed by the tremendous power which accumulated in the grasping hands of Dr. Harry Dexter White, who in 1953 was identified by Edgar Hoover as a Soviet agent. White assumed full responsibility for "all matters with which the Treasury Department has to deal having a bearing on foreign relations..." /5 He and his colleagues had Secretary Morgenthau's complete approval in the formulation of a blueprint for the permanent elimination of Germany as a world power. The benefits which might accrue to the Soviet Union as a result of such Treasury planning were incalculable.

When members of the Senate Internal Security sub committee asked Elizabeth Bentley, who was a courier between White and Soviet agents, whether she knew of a similar "Morgenthau Plan" for the Far East, she gave the following testimony:

Miss Bentley: No. The only Morgenthau Plan I knew anything about was the German one.

Senator Eastland: Did you know who drew that plan?

Miss Bentley: [It was] Due to Mr. White's influence, to push the devastation of Germany because that was what the Russians wanted.

Senator Ferguson: That was what the Communists wanted?

Miss Bentley: Definitely, Moscow wanted them [German factories] completely razed because then they would be of no help to the allies.

Mr. Morris: You say that Harry Dexter White worked on that?

Miss Bentley: And on our instructions he pushed hard. /6

When J. Edgar Hoover testified before the Subcommittee on November 17, 1953, he affirmed this testimony:

All information furnished by Miss Bentley, which was susceptible to check has proven to be correct. She had been subjected to the most searching of cross-examinations; her testimony has been evaluated by juries and reviews by the courts and has been found to be accurate.

Mr. Hoover continued:

Miss Bentley's account of White's activities was later corroborated by Whittaker Chambers; and the documents in White's own handwriting, concerning which there can be no dispute, lend credibility to the information previously reported on White. /7

Morgenthau hit the ceiling when he got a copy of the

Handbook for Military Government in Germany, which was designed for the guidance of every American and British official upon entering Germany. The

Handbook offered a glimpse of a very different kind of occupation that Treasury officials were hoping for. Its tone was moderate and lenient throughout Germany was not only to be self-supporting but was to retain a relatively high standard of living. Morgenthau wasted no time in showing the

Handbook to President Roosevelt, who immediately rejected its philosophy as too soft. Impressed by the critical memorandum White had prepared, the President killed the

Handbook and sent a stinging memorandum to the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, and a copy of which was sent to Hull. "This so-called Handbook is pretty bad," Roosevelt began, and he instructed that "all copies" be withdrawn immediately because it gave him the impression that Germany was to be "restored just as much as The Netherlands or Belgium, and the people of Germany brought back as quickly as possible to their pre-war estate." /8

Thus both Hull and Stimson were put on notice by the President that the State and War Departments must develop harsher attitudes towards Germany or be bypassed in the formulation of that policy. According to General Lucius Clay, suppression of the Handbook eventually had a "devastating effect on the morale of American officials responsible for disarming Germany." /9

Meanwhile the State Department and the Joint Chiefs of Staff had earlier completed their own prospectus and directive for postwar Germany. In the State document there was to be no "large-scale and permanent impairment of all German industry." /10 ICS 1067, as the military directive was numbered, was unmistakably akin in spirit to the "soft" State Department prospectus. Moreover, it was in "harmony" with the Handbook -- that is to say, this draft not only tolerated but actually encouraged friendly relations between American soldiers and German civilians. From various inter departmental meetings with State and War, a new version of JCS 1067 finally emerged. It completely reversed the spirit of the original draft. It was largely the handiwork of Harry Dexter White. It is indeed remarkable how the Treasury intervened and eventually got the State and War Departments to alter their basic policy on postwar Germany.

In the realm of finance, of course, the Secretary of Treasury would naturally be involved in the postwar treatment of Germany. But Morgenthau delved deeply into matters altogether unrelated to economics. The Germans needed psychiatry, Morgenthau told White. He said he was interested in "treating the mind rather than the body," and in planning "how to bring up the next generation of children." It might be wise to take the whole Nazi SS group out of Germany, he thought, and deport them to some other part of the world. "Just taking them bodily," he told White, and he "wouldn't be afraid to make the suggestion" even though it might be very "ruthless ... to accomplish the act." /11

Regarding the punishment of Nazi leaders, White suggested that a list of "war criminals" be prepared and presented to American officers on the spot, who could properly identify the guilty and shoot them on sight. Morgenthau remarked jokingly that a good start could be made with Marshal Stalin's "list of 50,000" -- a reference to Stalin's vodka toast to Roosevelt and Churchill at the Teheran Conference. /12

The disposition of the Ruhr Valley was one of the main topics discussed in one of the many Treasury meetings. For many years the coal fields of the Ruhr had been essential to the German economy. The British economist John Maynard Keynes had said after World War I that the Kaiser's empire was built "more truly on coal and iron than on blood and iron." /13 Coal was the backbone of all German industry, vital to her electric power and to her chemical, synthetic oil, and steel industries. /14 It was Morgenthau's persistent view, therefore, that the Ruhr should be "locked up and wiped out," and he was positive that the President was in "complete accord" on this point.

As the discussion proceeded, White shrewdly intimated that it might be better to place the Ruhr under international controls which would "produce reparations for twenty years." This was a straw proposal that Morgenthau promptly rejected. "Harry, you can't sell it to me at all," he said, "because it would be under control only a few years and the Germans will have another Anschluss!" The only program he would have any part of, Morgenthau declared, was "the complete shut-down of the Ruhr." When Harold Gaston, the Treasury public relations officer, interrupted to ask whether this meant "driving the population out," Morgenthau replied: "I don't care what happens to the population... I would take every mine, every mill and factory and wreck it." "Of every kind?" inquired Gaston. "Steel, coal, everything. Just close it down," Morgenthau said. "You wouldn't close the mines, would you?" inquired Daniel Bell, one of the Secretary's assistants. "Sure," replied Morgenthau, and he reiterated that the only economic activity which should remain intact was agriculture -- and that could be placed under some type of international control. He was for destroying Germany's economic power first, he said, and then "we will worry about the population second."

Morgenthau seemed very confident that the President would not waver in his support of a punitive program for postwar Germany. Any effective plan, however, would have to be executed within the next six months, or otherwise the Allies might suddenly become "soft." The best way to begin, Morgenthau advised, was to have American engineers go to every synthetic gas factory, and dynamite them or "open the water valves and flood them." Then let the "great humanitarians" simply sit "back and decide about the population afterwards." Eventually the Ruhr would resemble "some of the silver mines in Nevada," Morgenthau said. "You mean like Sherman's march to the sea?" asked Dan Bell. Morgenthau answered bluntly that he would make the Ruhr a "ghost area." /15

Such was the character of Secretary Morgenthau's views on the treatment of Germany. Never in American history had there been proposed a more vindictive program for a defeated nation. With the Treasury exerting unprecedented influence in determining American policy toward Germany, the fallacies of logic, evasion of issues and deliberate disregard of essential economic relationships manifest in the above conversation were incorporated in the postwar plan as finally adopted. Furthermore, no paper of any importance dealing with the occupation of Germany could be released until approved by the Treasury. The State and War Departments became virtually subservient to the Treasury in this area, normally their responsibility. /16

At a meeting in the President's office, Morgenthau and Stimson presented their opposite views. Stimson objected vigorously to the Treasury recommendation for the wrecking of the Ruhr. "I am unalterably opposed to such a program," he declared, holding it to be "wholly wrong" to deprive the people of Europe of the products that the Ruhr could produce. /17 The Treasury Plan, if adopted, would breed new wars, arouse sympathy for Germans in other countries, and destroy resources needed for the general reconstruction of ravaged Europe. He urged the President not to make a hasty decision, and to accept "for the time being" Hull's suggestion that the controversial economic issue be left for future discussion. /18

At the Quebec summit conference between Roosevelt and Churchill in September 1944, Morgenthau was asked to explain his plan to the British. Churchill was horrified and "in violent language" called the plan "cruel and un-Christian." But Morgenthau hammered on the idea that the destruction of the Ruhr would create new markets for Britain after the war. He also promised Churchill an American loan of $6.5 billion! Churchill "changed his mind" the next morning. /19

Although foreign affairs and military matters were discussed in depth at the Quebec Conference, neither Hull nor Stimson were in attendance. The Treasury Department took precedence over State and War in negotiations regarding Germany.

The effects of Morgenthau's victory at Quebec were quickly felt in Washington. At a luncheon with Undersecretary of War Robert Patterson, Morgenthau brought up the Quebec agreement. Patterson said jokingly: "To degrade Europe by making Germany an agricultural country, isn't that offensive to you?" Morgenthau replied: "Not in the case of Germany." /20

Hull felt strongly that Morgenthau should have been kept out of the field of general policy, and so did Stimson. When Stimson heard of the President's endorsement of the Treasury plan at Quebec, he quickly drafted another critical memorandum. "If I thought that the Treasury proposals would accomplish [our agreed objective, continued peace)," he wrote, "I would not persist in my objections. But I cannot believe that they will make for a lasting peace. In spirit and in emphasis they are punitive, not, in my judgment, corrective or constructive." He continued:

It is not within the realm of possibility that the whole nation of seventy million people, who have been outstanding for many years in the arts and the sciences and who through their efficiency and energy have attained one of the highest industrial levels in Europe, can by force be required to abandon all their previous methods of life, be reduced to a level with virtually complete control of industry and science left to other peoples ... Enforced poverty is even worse, for it destroys the spirit not only of the victim but debases the victor. It would be just such a crime as the Germans themselves hoped to perpetrate upon their victims -- it would be a crime against civilization iLself. /21

Word of "Morgenthau's coup at Quebec" leaked to the press with two results. One was that Roosevelt, because of the adverse reaction, evidently concluded that his Treasury Secretary had made "a serious blunder." The other was to stiffen German resistance on the Western front. Until then there was a fair chance that the Germans might discontinue resistance to American and British forces while holding the Russians at bay in the East in order to avoid the frightful fate of a Soviet occupation. This could have shortened the war by months and could have averted the spawning of malignant communism in East Germany.

How the Treasury officials were able to integrate basic features of their plan into the military directive, originally prepared by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and known as JCS 1067, is fully disclosed in the Diaries. White saw to it that many elements of his thinking were embodied in JCS 1067. Previous directives for guidance of American troops upon entrance into Germany, which already had undergone six or more revisions of a stylistic nature, were now brought more in line with the punitive thinking of Morgenthau and White. A new directive, which called for a more complete de-nazification, was, with some modifications, the spirit and substance of the Treasury plan. In the two full years that JCS 1067 was the cornerstone of American policy, Germany was punished and substantially dismantled in accord with the basic tenets of the Morgenthau Plan. JCS 1067 forbade fraternization by American personnel with the Germans, ordered a very strict program of de-nazification extending both to public life and to business, prohibited American aid in any rebuilding of German industry, and emphasized agricultural rehabilitation only.

Subsequently, JCS 1067 became a severe handicap to American efforts in Germany. It constituted what may be called without exaggeration a heavy millstone around the neck of the American military government. It gave only limited authority to to the United States military government by specifically prohibiting military officials from taking any steps to rehabilitate the German economy except to maximize agricultural production.

Through various channels, White had gathered information concerning the kind of policy directives other departments had in preparation. This he was able to achieve through a system of "trading" which Morgenthau had initiated at his suggestion. As Elizabeth Bentley told the Internal Security Subcommittee, "We were so successful getting information... largely because of Harry White's idea to persuade Morgenthau to exchange information." Treasury officials, for example, would send information to the Navy Department, and the Navy would reciprocate. There were, according to Miss Bentley, at least "seven or eight agencies" trading information with Morgenthau. /22

At the Yalta Conference on February 4, 1945, the question of postwar treatment of Germany was the most important item on the agenda. The President's conduct suggests the powerful effect on his thinking of White's masterplan and Morgenthau's salesmanship. On the major points regarding Germany the President easily capitulated to the Soviets. Stalin and Roosevelt were in general accord that the defeated Germans should be stripped of their factories and left to take care of themselves. But Churchill wished to preserve enough of the existing economic structure of Germany to permit the defeated nation to recover to some degree.

In his book

Beyond Containment, William H. Chamberlin assesses Yalta as a tragedy of appeasement:

Like Munich, Yalta must be set down as a dismal failure, practically as well as morally ... The Yalta Agreement represented, in two of its features, the endorsement by the United States of the principle of human slavery. One of these features was the recognition that German labor could be used as a source of reparations ... And the agreement that Soviet citizens who were found in the Eastern zones of occupation should be handed over to Soviet authorities amounted, for the many Soviet refugees who did not wish to return, to the enactment of a fugitive slave law. /23

After President Roosevelt returned from Yalta, State Department officials grasped an opportunity to push through their own program for postwar Germany. On March 10, 1945, Secretary of State Edward Stettinius submitted for the President's consideration the draft of a new policy directive for the military occupation of Germany. The prime movers in this strategy were Leon Henderson, James C. Dunn, and James W. Riddleberger, the departmental expert on German affairs. They purposely did not consult with Treasury officials because they knew there would be major objections from them. The March 10 memorandum was a reasonable substitute for the rigorous JCS 1067, which was so pleasing to White and Morgenthau. It was based on the central concept that Germany was important to the economy recovery of Europe. It provided for joint allied control of defeated Germany, preservation of a large part of German industry, and a "minimum standard of living" for the German people. The memorandum had no provision for dismemberment, and Germany was to begin "paying her own way as soon... as possible." /24

When Morgenthau saw a copy of the State Department memorandum, he became so furious that he immediately telephoned Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy to voice his complaints. "It's damnable, an outrage!" he exclaimed. "Riddleberger and these fellows are just putting this thing across ... I'm not going to take it lying down." The State Department plan, if adopted, would have spelled complete defeat for Morgenthau and White. "It makes me so mad," Morgenthau raged, "I think the President should fire Jimmy Dunn and two or three other fellows." /25

Several days later, armed with a memorandum drafted by White, Coe, and Glasser, he hurried to the White House. He was disturbed to find Roosevelt's daughter, Anna, and her husband, Maj. John Boettinger, caring for the President, "whose health by that time was faltering to the point where mental lapses could be expected." Roosevelt apparently no longer thought that Morgenthau had "pulled a boner" with his destroy-Germany plan and when Boettinger commented "You don't want the Germans to starve," the President replied "Why not?" Morgenthau told White he was worried about Boettinger's attitude. The question one may ask is did the Soviets know what the American people did not know -- that Roosevelt was close to death and liable to blackouts at any moment?

Morgenthau reported jubilantly, however, to his "team" that the President had accepted his plan as "a good tough document." He confided in his diary:

We have a good team, they just can't break the team... It is very encouraging that we had the President back us up... they tried to get him to change and they couldn't -- the State Department crowd. Sooner or later, the President just has to clean his house. I mean the vicious crowd... They are Fascists at heart... /26

The State Department was sorely disappointed that the President had rejected their March 10th memorandum. It was a severe defeat for Riddleberger, Dunn, and others who were advocating a reasonable program for Germany. Morgenthau felt that the new JCS document should declare unmistakably that the State Department paper of March 10 was officially withdrawn. White asked McCloy and General Hilldring whether everyone in the War Department would understand that the new document "superseded" the March 10 memorandum. McCloy assured him that everyone would be duly notified. White then asked whether it would be perfectly "clear" in the Army that the Treasury document "took precedence over and caused the revision of any document contrary to it." General Hilldring answered there would be no problem here.

A cardinal point of dispute between the Treasury and the Department of War resided in the question of the treatment of German war criminals. Stimson advised the President to have trials rather than the "shoot on sight" policy advocated by Morgenthau. Stimson believed the accused should have a right to be heard and be allowed to call witnesses to his defense. /27 Another subject of controversy between the Treasury on the one side and the State and War on the other was the question of reparations. The Treasury believed that reparations should be limited to whatever the Allies could wring out of defeated Germany at the end of the war. Morgenthau and White were dead set against the old concept of long-term reparations payments, because such annual tribute would necessitate the re-building of industry on a large scale in Germany. They wished to make the Germans "pastoral" and then throw upon them the full responsibility for taking care of themselves. The World War I application of "reparations" would result in nothing more or less that the revitalization of German industrial might. In their thinking this specter loomed large indeed.

White and his colleagues were careful not to jeopardize postwar relations with the Soviet Union. They frequently expressed their fears of Western encirclement of Russia. They thought that those individuals in the American government who wished to restore Germany were motivated by the idea that a strong Reich was necessary as a "bulwark against Russia." This attitude was certainly responsible for many of the current difficulties between Washington and Moscow. At one of the interdepartmental meetings a dispute developed over the question of compulsory German labor as restitution for war damages in Russia. Treasury officials were boldly advocating the creation of a large labor force with no external controls. This view was challenged by War, State and other departments as treating two or three million people as slave labor. Morgenthau reminded his opponents that the whole issue of compulsory labor had already been decided upon at Yalta. "We are simply carrying out the Yalta agreement," he exclaimed, and anyone who is going to protest "... is protesting against Yalta ..." It is significant that five months previously, President Roosevelt had sent a memorandum to Morgenthau to the effect that if "they [Russia] want German labor, there is no reason why they should not get it in certain circumstances and under certain conditions." /28

White opined that if the Russians needed two million German laborers to reconstruct their devastated areas, he saw nothing wrong with it; it was "in the interest" of Russia and even Germany that the labor force come from the ranks of the Gestapo, the S.S., and the Nazi party membership. "That's not a punishment for crime," he stated, "that's merely a part of the reparations problem in the same way you want certain machines from Germany... /29

As long as Morgenthau was Secretary of the Treasury, White performed adroitly in his strange Svengali role. But fundamental changes in the management of American foreign policy occurred after Harry Truman became President. While the President was still a Senator, he read in the newspapers about the Morgenthau Plan, and he didn't like it. Morgenthau wanted to come to Potsdam, threatening to resign if he was not made a member of the U.S. delegation. Truman promptly accepted his resignation.

What were the final results of the Morgenthau Plan? What actual effect did it have on Germany? "While the policy was never fully adopted," wrote W. Friedmann, "it had a considerable influence upon American policy in the later stages of the war and during the first phase of military government." /30 Although President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill eventually recognized the folly of what they had approved at Quebec, Morgenthau, White, and the Treasury staff saw to it that the spirit and substance of their plan prevailed in official policy as it was finally mirrored in the punitive directive known as JCS 1067.

In a very definite way JCS 1067 determined the main lines of U.S. policy in Germany for fully two years after the surrender. Beginning in the fall of 1945, to be sure, a new drift in American policy was evident, and it eventually led to the formal repudiation of the directive in July of 1947. Until it was officially revoked, however, the lower administrative echelons had to enforce its harsh provisions. "The military government officers," writes Prof. Harold Zink, "were unable to see how Germany could be reorganized without a substantial amount of industrialization. They tried to fit the Morgenthan dictates into their economic plans, but they ended up more or less in a state of paralysis." /31

As White had certainly anticipated, the economic condition of Germany was desperate between 1945 and 1948. The cities remained heaps of debris, and shelter was at a premium as a relentless stream of unskilled refugees poured into the Western zones, where the food ration of 1,500 calories per day was hardly sufficient to sustain life. As Stimson, Riddleberger, and others had predicted, the economic prostration of Germany now resulted in disruption of the continental trade that was essential to the prosperity of other European nations. As long as German industrial power was throttled, the economic recovery of Europe was delayed -- and this, in time, led to serious political complications. To nurse Europe back to health, the Marshall Plan was devised in 1947. It repudiated, at long last, the philosophy of the White-Morgenthau program.

The currency reforms of June 1948 changed the situation overnight. These long overdue measures removed the worst restraints, and thereupon West Germany began its phenomenal economic revival.

After all this has been said, an implicit question haunts the historian. It is this: if the Morgenthau Plan was indeed psychopathically anti-German, was it also consciously and purposefully pro-Russian? The Secretary of the Treasury never denied that his plan was anti-German in both its philosophy and its projected effects, but no one in his department ever admitted that it was also pro-Russian in the same ways. In his book,

And Call It Peace, Marshall Knappen suggested in 1947 that the Morgenthau Plan "corresponded closely to what might be presumed to be Russian wishes on the German question. It provided a measure of vengeance and left no strong state in the Russian orbit." /32

In document after document the Diaries reveal Harry Dexter White's influence upon both the formative thinking and the final decisions of Secretary Morgenthau. Innocent of higher economics and the mysteries of international finance, the Secretary had always leaned heavily on his team of experts for all manner of general and specific recommendations. /33 White was the field captain of that team; on the German question he called all the major plays from the start. As a result of White's advice, for example, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing was ordered in April 1944 to deliver to the Soviet government a duplicate set of plates for the printing of the military occupation marks which were to be the legal currency of postwar Germany. The ultimate product of this fantastic decision was to greatly stimulate inflation throughout occupied Germany, and the burden of redeeming these Soviet-made marks finally fell upon American taxpayers to a grand total of more than a quarter of a billion dollars. /34 White followed this recommendation with another, in May of 1944, which again anticipated the emerging plan. This time he urged a postwar loan of ten billion dollars to the Soviet Union. /35

Remember that, in her testimony before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee in 1952, the confessed Communist courier Elizabeth Bentley charged that White was the inside man who prepared the plan for Secretary Morgenthau, and "on our instruction he pushed hard." Also, J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI charged that White was an active agent of Soviet espionage, and despite the fact he had sent five reports to the White House warning the President of White's activities, Truman promoted him to a position at the United Nations. When the shocking story of White's service as a Soviet agent was first revealed by Attorney General Herbert Brownell in a Chicago speech, it created quite a stir of public charges and counter-charges by then retired Harry Truman.

The concentration of Communist sympathizers in the Treasury Department is now a matter of public record. White eventually became Assistant Secretary. Collaborating with him were Frank Coe, Harold Glasser, Irving Kaplan and Victor Perlo, all of whom were identified in sworn testimony as participants in the Communist conspiracy. When questioned by Congressional investigators, they consistently invoked the Fifth Amendment. In his one appearance before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1948, White emphatically denied participation in any conspiracy. A few days later he was found dead, the apparent victim of a heart attack (which is questioned by some investigators). Notes in his handwriting were later found among the "pumpkin papers" on Whittaker Chambers' farm. /36 In a statement before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee in 1953, Attorney General Brownell declared White guilty of "supplying information consisting of documents obtained by him in the course of duties as Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury, to Nathan Gregory Silvermaster..." /37 Silvermaster passed these documents on to Miss Bentley after photographing them in his basement. When asked before two congressional committees to explain his activities, Silvermaster invoked the Fifth Amendment.

Never before in American history had an unelected bureaucracy of faceless, "fourth floor" officials exercised such arbitrary power over the future of nations as did Harry Dexter White and his associates in the Department of the Treasury under Henry Morgenthau, Jr. What they attempted to do in their curious twisting of American ideals, and how close they came to complete success, is demonstrated in the Morgenthau Diaries, which I had the privilege of examining and which were published by the Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, in 1967.

Notes

- John Morton Blum, Years of Urgency, 1938-41: From the Morgenthau Diaries (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Co., 1965), p. 3.

- The Memoirs of Cordell Hull (New York: Macmillan Co., 1948), VoL 1, pp. 207-208.

- Ibid., 1, p. 207

- Issue of September 5, 1946.

- December 15, 1941, Interlocking Subversion in Government Departments, Final Report, July 30, 1953, p. 29.

- Institute of Pacific Relations, pt 2, pp. 419-420.

- Interlocking Subversion in Government Departments, pt. 16, p. 1145.

- August 26, 1944, Book 766, pp. 166-170. Morgenthau Diaries, Hyde Park.

- Lucius Clay, Decision in Germany (New York, Doubleday and Co.1950), p. 8.

- Book 777, p. 70 et seq.

- August 28, 1944, Book 767, p. 1.

- September 4, 1944, Book 768, p. 104.

- John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (New York~ Harcourt Brace and Co. 1920), p. 81.

- B.H. Klein, Germany's Economic Preparations for War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959), p. 123. 15.

- September 4, 1944, Book 768, p. 104.

- November 21, 1944, Book 797, pp. 256-258.

- September 9, 1944, Book 771, p. 50.

- Ibid.; Henry L. Stimson and McGeorge Bundy, On Active Service in Peace and War (New York, Harper and Row, 1948), pp. 573-574.

- October 18-19, 1944, Book 783, pp. 23-39.

- September 27, 1944, Book 776, p. 33.

- September 15, 1944, Book 772, pp. 4-9. (Italics mine.)

- Institute of Pacific Relations, Hearings, pt. 2, p. 422.

- (Chicago: Henry Regnery Co., 1953), pp. 36-46.

- March 10, 1945, Book 827-1, pp. 1-2.

- March 19, 1945, Book 828-2, p. 233; March 20, 1945, Book 830, p. 24.

- March 23, 1945, Book 831-2, p. 205, et seq.

- September 9, 1944, Book 771, p. 50 et seq.

- December 9, 1944, Book 802, pp. 241-248.

- May 18, 1945, Book 847, pp. 293-299.

- W. Friedmann, The Allied Military Government of Germany (London: Stevens and Sons, Ltd., 1947), p. 20.

- Harold Zink, American Military Government in Germany (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1947), pp. 187-189.

- Marshall Knappen, And Call It Peace (University of Chicago Press, 1947), pp. 53-56.

- The Secret Diary of Harold L. Ickes: The First Thousand Days (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1953), I. 331.

- For this strange story in detail, see Transfer of Occupation Currency Plates -- Espionage Phase, Interim Report of the Committee on Government Operations, December 15, 1953 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1953).

- May 16, 1944, Book 732, pp. 97-99.

- Interlocking Subversion in Government Departments, pt. 16.

- Ibid., pt. 16, pp. 1110-1141.

From

The Journal of Historical Review, Fall 1989 (Vol. 9, No. 3), pages 287-303.

This article was presented by Prof. Kubek at the Ninth IHR Conference, February 1989, in Huntington Beach, California.

About the Author

Anthony Kubek (1920-2003) was a nationally prominent authority on American foreign policy, especially US policy in Asia. He earned three degrees from Georgetown University, including a Ph.D. in American Diplomatic History (1956). During his academic career, he served as the Academic Dean of Frisco College, in Frisco, Texas, and as a professor at the University of Dallas, where he was chairman of the Department of History and Political Science. His published writings included

The Amerasian Papers, a two-volume study issued by the US Senate Committee on the Judiciary,

How the Far East was Lost: American Policy and the Creation of Communist China, 1941- 1949 (published in 1963 and 1972), and

The Red China Papers (1975).