The Sears & Roebuck schools were all built especially for blacks who were already living in segregated areas.

"[Sears & Roebuck's Jewish tycoon, Julius] Rosenwald died in 1932, and soon after his fund wound down—as he intended—leaving a legacy of 5,357 schoolhouses, shop buildings, and teachers’ homes across the South, from Florida to Maryland and Texas."

Frank Lloyd Wright designed the Rosenwald schools which 5,357 were then built. After decades of little building maintenance in black communities, the schools fell into disrepair. Just like any area where the population is majority black, it all goes to s#it. The blacks were given over 5,300 schools, which were all stocked with books, etc.

The blacks complain, always trotting out their BS about getting old books, even if they were old books, the contents were standards.

The Topeka, Kansas study is always ignored. Majority of blacks did not want desegregation, the ones who did were involved with Jews.

DESEGREGATION CREATED HUGE BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES FOR JEWS.

I believe the constant black complaints are just a cover for black low IQ, as more modern studies explained in The Bell Curve.

Constant change, especially radical ongoing change such as desegregation only covers up the real problems of low IQ and a black predisposition of, acting black, or even blacks criticized for 'acting white'.

###

https://www.architectmagazine.com/design/culture/remembering-the-rosenwald-schools_o

Remembering the Rosenwald Schools

How Julius Rosenwald and [black] Booker T. Washington created a thriving schoolhouse construction program for African Americans in the rural South.

CIESLA Foundation

The renovated Ridgeley Rosenwald school in Capitol Heights, Md., now operating as a museum

Before there was Samuel Mockbee and Rural Studio, there was

Julius Rosenwald.

In the early 1900s, Rosenwald oversaw a self-help construction program for schoolhouses in the rural South. By 1928, one out of every five schools in the region was what became popularly known as a Rosenwald School.

Courtesy Special Collections Res

Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington, circa 1915

Rosenwald was not an architect. He was a tycoon, the man who turned Sears, Roebuck & Co. from a small Chicago-based mail-order house into the largest merchandiser in the country. Like many American tycoons, he was a philanthropist.

The son of poor German-Jewish immigrants—his father was a peddler—

Rosenwald had experienced anti-Semitism, and he was particularly sensitive to the plight of black Americans. After reading Up from Slavery, he sought out Booker T. Washington and became a major benefactor of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

The meeting of Rosenwald and Washington is a pivotal moment in

a new documentary, released this summer, by the Washington, D.C.–based filmmaker Aviva Kempner, whose work includes

Partisans of Vilna (1986) and the Emmy-nominated

The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg (1998).

Rosenwald, which premiered at New York City’s Center for Jewish History and was screened at the NAACP’s recent national convention in Philadelphia, is a Horatio Alger story of accomplishment, practical idealism, vile segregation, and self-help construction.

A Rosenwald school in Taylors, S.C., circa 1940

In 1912, in reaction to the substandard conditions of black rural schools in the Jim Crow South, Booker T. Washington enlisted his friend Rosenwald’s support in building six new schools for black children in Alabama. Rosenwald was so impressed with the results that he proposed enlarging the program. He first suggested that Sears could manufacture schools as prefabricated kits—similar to the famous Sears catalog homes—but Washington insisted that design and construction of the buildings should be handled locally, to guarantee the active involvement of the community. To that end, Rosenwald donated part of the cost of each building, requiring matching funds to be raised by local school boards and the black community.

As Booker T. Washington intended, the design and construction of the Rosenwald Schools were left to the local community, but guidance was provided in the form of technical advice and practical handbooks. In 1915, Tuskegee published The Negro Rural School and Its Relation to the Community, which included building designs by Robert Robinson Taylor. An architect and the first black graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (in 1892), Taylor designed more than 20 buildings on the Tuskegee campus. Following Washington’s strict self-help philosophy, these were built by the students themselves; student masons manufactured bricks, student carpenters felled trees and dressed lumber. Taylor was effectively the second-in-command at Tuskegee, but he was also responsible for a number of buildings at other southern black universities, as well as the impressive Renaissance Revival Colored Masonic Temple in Birmingham, Ala.

Fisk University; The Hickstown Rosenwald school in Durham County, N.C.

Booker T. Washington died only two years after the first rural schools were built, but the newly created Rosenwald Fund enabled the program to continue. Rosenwald relied on the advice of Fletcher Bascom Dresslar, a Berlin-trained professor of health education at George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville. Dresslar had definite ideas about architecture. He deplored “gingerbread stuff,” and especially disliked belfries—a staple of the traditional country schoolhouse. “Thus far the architects of the large majority of our smaller schools have clung tenaciously to the ‘schoolhouse type,’ and have given us, in the main, buildings devoid of any attempt at niceties of proportion or unity of design,” he wrote in his how-to guide,

American Schoolhouses (1911).

Dresslar, who emphasized “beauty of proportion and fitness for use,” was a confirmed functionalist. But unlike the work of Rural Studio, which tends to be self-consciously avant-garde,

the Rosenwald Schools were decidedly traditional in appearance: pitched roofs, deep overhangs, porches, and white-washed clapboard siding. The ordinariness was intentional. It made sense to follow well-understood building practices and to avoid needless complexity, because the schools were often built by unskilled volunteer labor. It also made sense to use an architectural language that was familiar to the users. Yet the completed buildings are not without art. Following Dresslar’s teaching, decorative trim was kept to a minimum, which gives these unadorned buildings a satisfying, Shaker-like simplicity.

A Rosenwald school in Alabama

The Rosenwald Schools may have looked traditional, but they incorporated many design innovations. The classrooms were often separated by movable partitions so they could be combined into one large space. The most common arrangement was two classrooms, an adjacent “industrial room” for shop and cooking classes, as well as vestibules and cloakrooms. (So-called community schools had more classrooms, and included an auditorium as well as a library.) Classrooms had tall ceilings and exceptionally large double-hung windows, typically arranged in batteries for maximum daylighting, which was crucial since many of the sites lacked electricity. East and west light was favored and building orientation was emphasized. “It is better to have proper lighting within the schoolroom, however, than to yield to the temptation to make a good show by having the long side face the road,”

instructed the Tuskegee handbook. Cross-ventilation was facilitated by “breeze windows”—internal openings—and the buildings were raised off the ground on piers to facilitate cooling. This was green architecture by necessity.

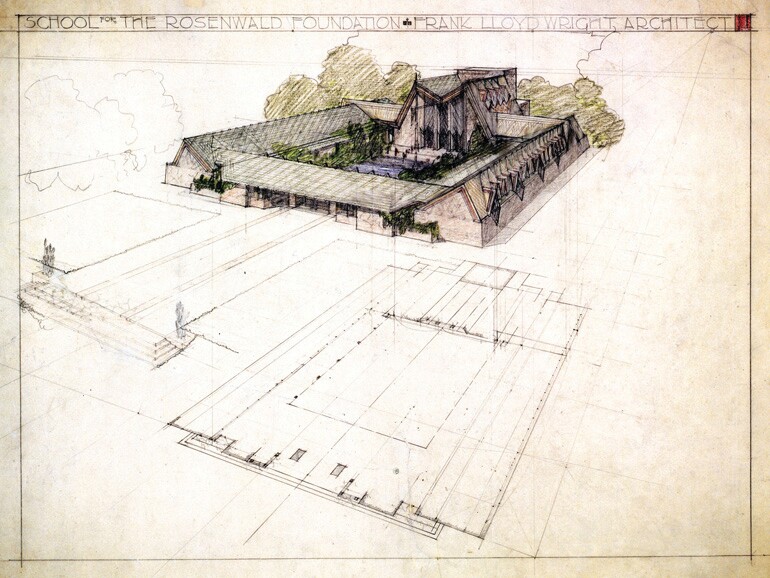

©Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation; Frank Lloyd Wright's 1928 design for a Rosenwald School

One should not imagine that Rosenwald was architecturally timid. He built the first Sears Tower, which was attached to a huge merchandise building that was known as “the world’s largest store.” When he conceived the Michigan Boulevard Garden Apartments in Chicago, intended for middle-class African Americans, he was inspired by a socialist housing project that he had seen in Vienna. His own home in Kenwood was a Prairie Style mansion designed by George C. Nimmons, who had apprenticed with Daniel Burnham.

One of Rosenwald’s friends and a fellow supporter of Tuskegee who was particularly interested in architecture was Darwin D. Martin of Buffalo, N.Y. Martin was a long-time patron of Frank Lloyd Wright (the Larkin Building, the Martin House), and in 1928 he convinced Wright to submit a design for a Rosenwald School. The site was the campus of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, a historically black college (and Booker T. Washington’s alma mater). Wright dismissed Shaker-like simplicity as the “extreme of timidity,” and produced an unusual courtyard scheme. The courtyard, which included a swimming pool, was dominated by a tall children’s theater with balconies, a proscenium stage, and a fly tower. The classrooms were lit by east- and west-facing dormer windows. The unconventional construction of heavy concrete and fieldstone, which Wright would later use at Taliesin West in Arizona, was an odd choice for a Southern campus. “Never built. Not ‘Colonial,’ ” Wright scrawled on his study drawing. “Never built. Too expensive” was probably closer to the truth.

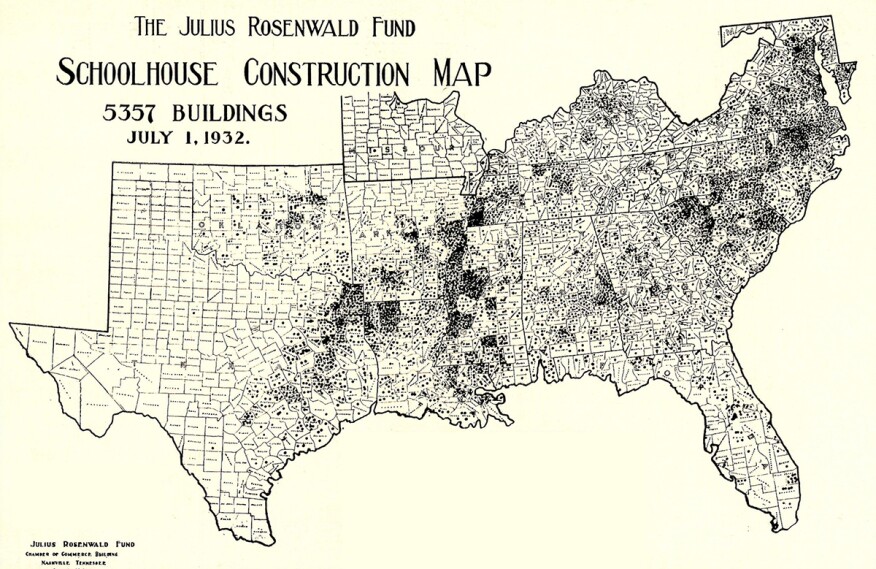

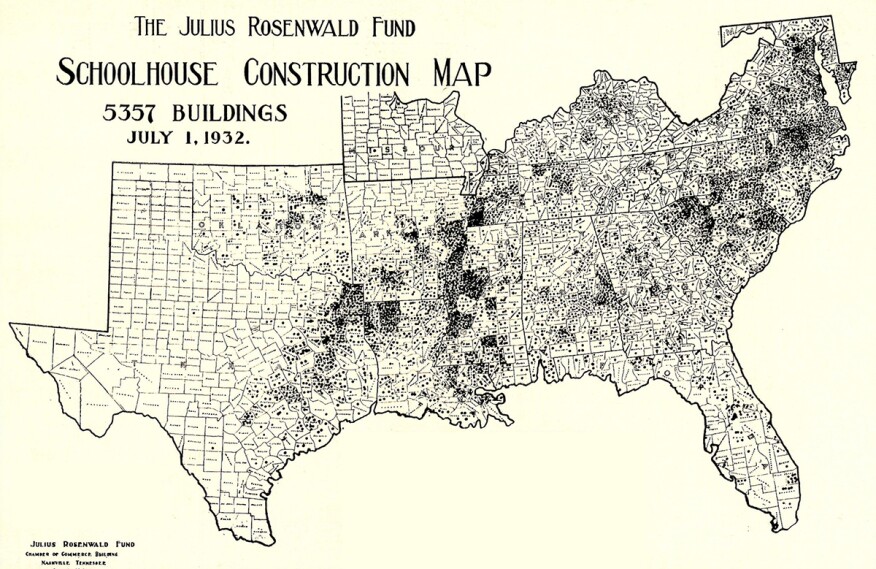

A 1932 map illustrating how widespread the schools were across the South

Rosenwald died in 1932, and soon after his fund wound down—as he intended—leaving a legacy of 5,357 schoolhouses, shop buildings, and teachers’ homes across the South, from Florida to Maryland and Texas. The reaction of white communities to Rosenwald Schools was predictable: a few cases of arson, occasional vandalism, and general neglect. Nevertheless, most of the schools remained in active use until the 1960s, when the desegregation mandated by Brown v. Board of Education went into effect. Several illustrious Rosenwald alumni are interviewed in Kempner’s film, including Maya Angelou, Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), and

Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson.

Earl Leatherberry via Flickr Cre The Russell School in Durham County, N.C., constructed according Rosenwald's two-teacher plan

Although more than two score Rosenwald Schools have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, many have been demolished or allowed to fall into disrepair. The National Trust for Historic Preservation is committed to preserving a hundred Rosenwald Schools and currently offers grants to assist in their rehabilitation. Restored, the buildings have found use as community centers, senior centers, town halls, and local museums.

The Rosenwald Schools recall the heroic efforts of exceptional individuals during a particularly dark period in the nation’s history. They are also a graphic reminder of a time when great philanthropy and architecture went hand in hand: Andrew Carnegie and his libraries; Andrew Mellon and the National Gallery of Art; Edward Harkness at Harvard and Yale; and, not least, Julius Rosenwald and his rural schoolhouses.