-----------------------------------------------[HERE'S PART 2 TO ABOVE]-------------------------------------------------

Exposing the War-Makers

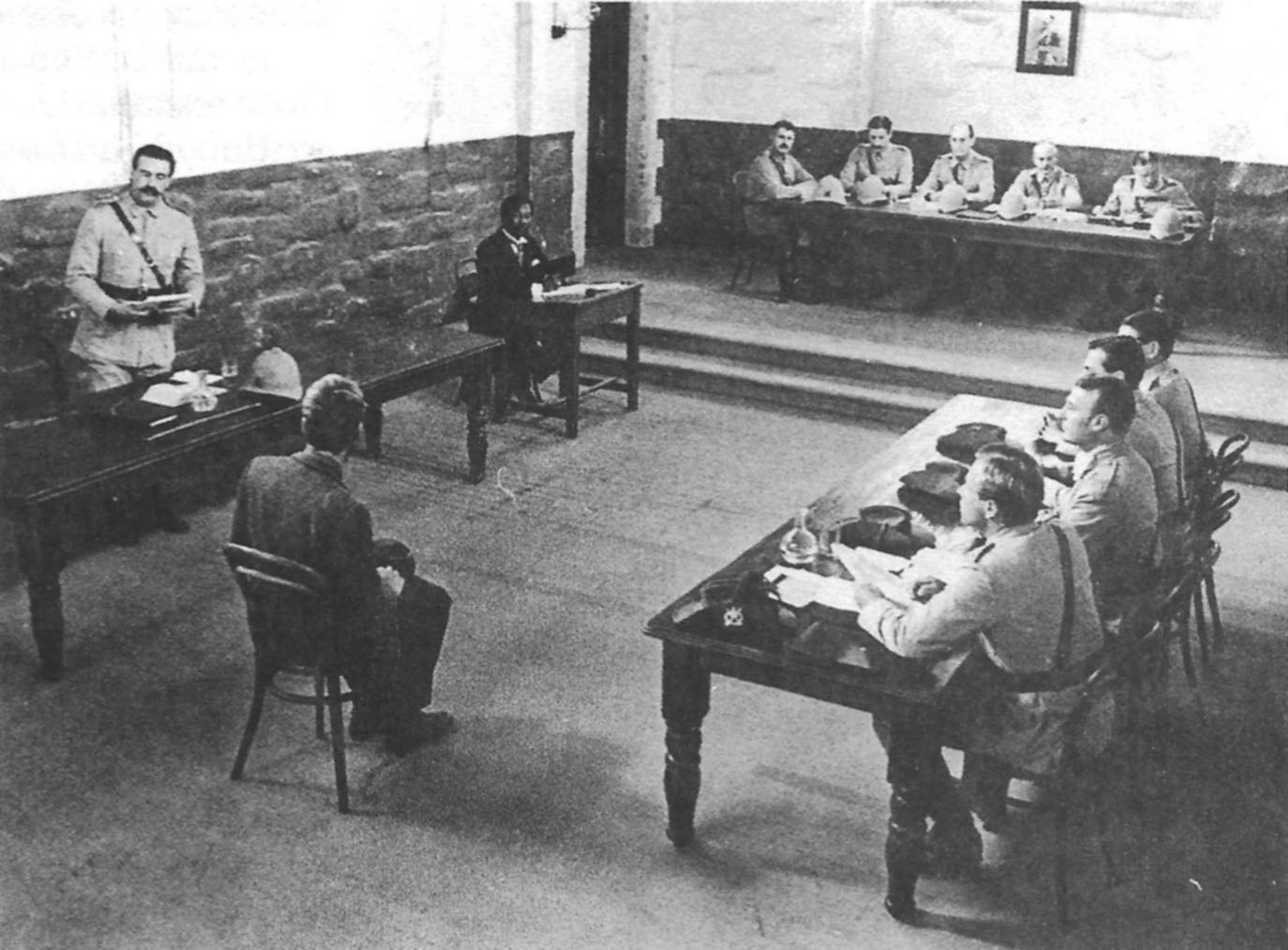

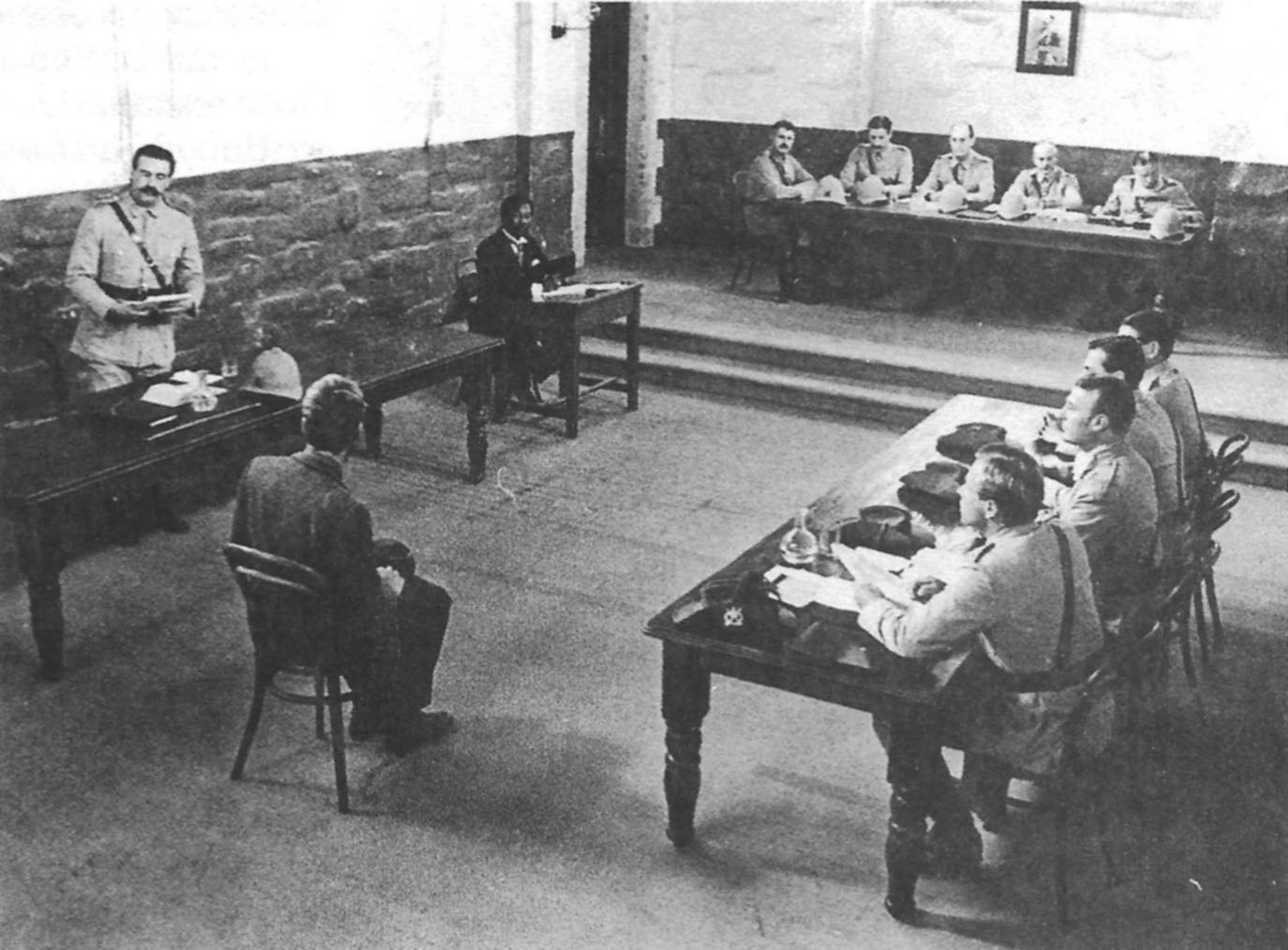

Courtroom scene from the 1980 Australian film “Breaker Morant,” which highlighted the British policy of shooting Boer prisoners during the war in South Africa. The film dramatized the case of several Australians serving with the Bush Veldt Carbineers, a special “anti-commando” unit, who were tried and executed in February 1902 for having shot twelve Boer prisoners. In the award-winning film, Edward Woodward played the role of Lt. “Breaker” Morant.

In the United States, as in most of Europe, public interest in the conflict was keen. Although public sentiment in these countries was largely pro-Boer and anti-British, the government leaders — fearful of the adverse consequences of defying Britain — were publicly pro-British, or at least studiously neutral.

William Jennings Bryan, Andrew Carnegie and many other Americans were embarrassed by the striking parallel between US and British policy of the day: just as Britain was forcibly subduing the Boers in southern Africa, American troops were brutally suppressing native fighters for independence in the newly-acquired Philippines. Echoing a widespread American sentiment of the day, Mark Twain declared: “I think that England sinned when she got herself into a war in South Africa which she could have avoided, just as we have sinned in getting into a similar war in the Philippines.” In spite of such sentiment, the government of President McKinley and the jingoistic newspapers of William Randolph Hearst sided with Britain.

note 33

But even in Britain itself, there was considerable opposition to the war. In the House of Commons, Liberal MP Philip Stanhope (later Baron Weardale) introduced a resolution expressing disapproval of Britain’s military campaign against the Boer republics. In tracing the war’s origins, he said:

note 34

Accordingly, the [pro-British] South African League was formed, and Mr. Rhodes and his associates — generally of the German Jew extraction — found money in thousands for its propaganda. By this league in [British] South Africa and here [in Britain] they have poisoned the wells of public knowledge. Money has been lavished in the London world and in the press, and the result has been that little by little public opinion has been wrought up and inflamed, and now, instead of finding the English people dealing with this matter in a truly English spirit, we are dealing with it in a spirit which generations to come will condemn …

Opposition in Britain to the war came especially from the political left. The Social Democratic Federation (SDF), led by Henry M. Hyndman, was especially outspoken.

Justice, the SDF weekly, had already warned its readers in 1896 that “Beit, Barnato and their fellow-Jews” were aiming for “an Anglo-Hebraic Empire in Africa stretching from Egypt to Cape Colony, designed to swell their “overgrown fortunes.” Since 1890, the SDF had repeatedly cautioned against the pernicious influence of “capitalist Jews on the London press.” When war broke out in 1899,

Justice declared that the “Semitic lords of the press” had successfully propagandized Britain into a “criminal war of aggression.”

note 35

David Lloyd George, an influential Member of Parliament who would later serve as his country’s Prime Minister during the First World War, accused Britain of waging a “war of extermination” against Boer women and children.

Opposition to the war was similarly strong in the British labor movement. In September 1900, the Trades Union Congress passed a resolution condemning the Anglo-Boer war as one designed “to secure the gold fields of South Africa for cosmopolitan Jews, most of whom had no patriotism and no country.”

note 36

No member of the House of Commons spoke out more vigorously against the war than John Burns, Labour MP for Battersea. The former SDF member had gained national prominence as a staunch defender of the British workingman during his leadership of the dockworkers’ strike of 1889. “Wherever we examine, there is the financial Jew,” Burns declared in the House on February 6, 1900, “operating, directing, inspiring the agencies that have led to this war.”

“The trail of the financial serpent is over this war from beginning to end.” The British army, Burns said, had traditionally been the “Sir Galahad of History.” But in Africa it had become the “janissary of the Jews.”

note 37

Burns was a legendary fighter for the rights of the British worker, a tireless champion of environmental reform, women’s rights and improved municipal services. Even Cecil Rhodes had referred to him as “the most eloquent leader of the British democracy.” It was not merely the Jewish role in Capitalism that alarmed Burns. To his diary he once confided that “the undoing of England is within the confines of our afternoon journey amongst the Jews” of East London.

note 38

Irish nationalist Members of Parliament had special reason to sympathize with the Boers, whom they regarded — like the people of Ireland — as fellow victims of British duplicity and oppression. One Irish MP, Michael Davitt, even resigned his seat in the House of Commons in “personal and political protest against a war which I believe to be the greatest infamy of the nineteenth century.”

note 39

At the age of 23, Cecil Rhodes wrote of his great goal: “Why should we not form a secret society with but one object, the furtherance of the British Empire and the bringing of the whole uncivilized world under British rule, for the recovery of the United States, for the making the Anglo-Saxon race but one Empire? What a dream, but yet it is probable, it is possible,” (Source: A. Thomas, “Rhodes,” 1997, p. 6.)

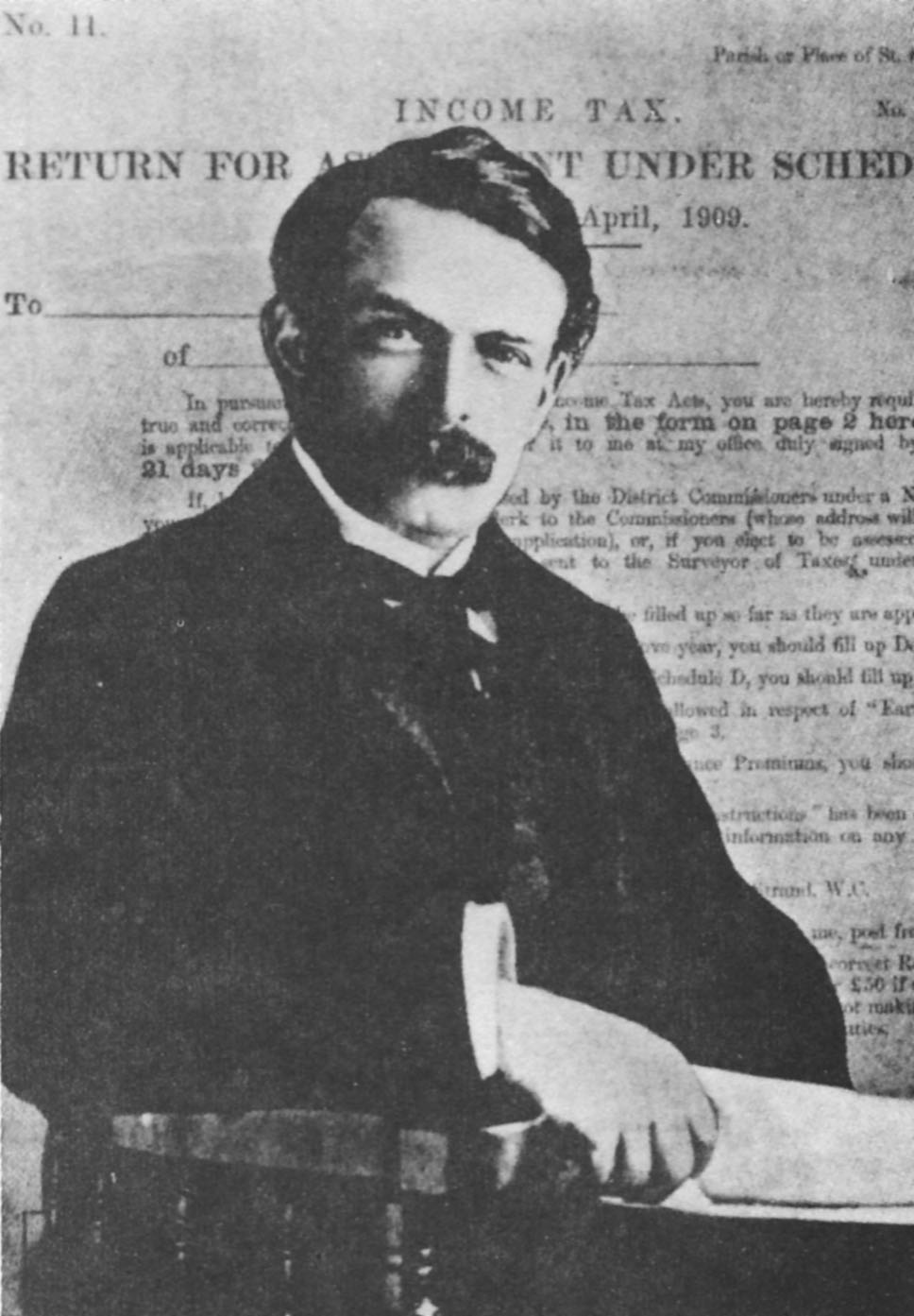

One of the most influential campaigners against the “Jew-imperialist design” in South Africa was John A. Hobson (1858-1940), a prominent journalist and economist.

note 40 In 1899 the

Manchester Guardian sent him to South Africa to report first-hand for its readers on the situation there. During his three month investigation, Hobson became convinced that a small group of Jewish “Randlords” was essentially responsible for the strife and conflict.

note 41

In a

Guardian article dispatched from Johannesburg just a few weeks before the outbreak of the war, he told readers of the influential liberal daily:

note 42

In Johannesburg the Boer population is a mere handful of officials and their families, some five thousand of the population; the rest is about evenly divided between white settlers, mostly from Great Britain, and the [native black] Kaffirs, who are everywhere in White Man’s Africa the hewers of wood and the drawers of water.

The town is in some respects dominantly and even aggressively British, but British with a difference which it takes some little time to understand. That difference is due to the Jewish factor. If one takes the recent figures of the census, there appears to be less than seven thousand Jews in Johannesburg, but the experience of the street rapidly exposes this fallacy of figures. The shop fronts and business houses, the market place, the saloons, the “stoops” of the smart suburban houses and sufficient to convince one of the large presence of the chosen people. If any doubt remains, a walk outside the Exchange, where in the streets, “between the chains,” the financial side of the gold business is transacted, will dispel it.

So far as wealth and power and even numbers are concerned Johannesburg is essentially a Jewish town. Most of these Jews figure as British subjects, though many are in fact German and Russian Jews who have come to Africa after a brief sojourn in England. The rich, rigorous, and energetic financial and commercial families are chiefly English Jews, not a few of whom here, as elsewhere, have Anglicised their names after true parasitic fashion. I lay stress on this fact because, though everyone knows the Jews are strong, their real strength here is much underestimated. Though figures are so misleading, it is worth while to mention that the directory of Johannesburg shows 68 Cohens against 21 Joneses and 53 Browns.

The Jews take little active part in the Outlander agitation; they let others do that sort of work. But since half of the land and nine-tenths of the wealth of the Transvaal claimed for the Outlander are chiefly theirs, they will be chief gainers by an settlement advantageous to the Outlander.

In an influential book published in 1900,

The War in South Africa, Hobson warned and admonished his fellow countrymen:

note

43

We are fighting in order to place a small international oligarchy of mine-owners and speculators in power at Pretoria. Englishmen will surely do well to recognize that the economic and political destinies of South Africa are, and seem likely to remain, in the hands of men most of whom are foreigners by origin, whose trade is finance, and whose trade interests are not chiefly British.

Anti-imperialist and working-class circles acclaimed Hobson’s widely read work. Commenting on it, the weekly

Labour Leader, semi-official organ of the Independent Labour Party, noted: “Modern imperialism is really run by half a dozen financial houses, many of them Jewish, to whom politics is a counter in the game of buying and selling securities.”

note 44 In a January 1900 essay,

Labour Leader editor (and MP) J. Keir Hardie told readers:

note 45

The war is a capitalist’ war, begotten by capitalists’ money, lied into being by a perjured mercenary capitalist press, and fathered by unscrupulous politicians, themselves the merest tools of the capitalists … As Socialists, our sympathies are bound to be with the Boers. Their Republican form of Government bespeaks freedom, and is thus hateful to tyrants …

Defeat

As the year 1900 drew to a close, British forces held the major Boer towns, including the capitals of the two republics, as well as the main Boer railway lines. Paul Kruger, the man who personified his people’s resistance to alien rule, had been forced into exile. By the end of 1901, the Boers’ military forces had been reduced to some 25,000 men in the field, deployed in scattered and largely un-coordinated commando units. The hard-pressed defenders had only a shadow of a central government.

In the spring of 1902, with their land almost entirely under enemy occupation, and their remaining fighters threatened with annihilation and militarily outnumbered six to one, the Boers sued for peace. On May 31, 1902, their leaders concluded 33 months of heroic struggle against greatly superior forces by signing a treaty that recognized King Edward VII as their sovereign. President Kruger learned of the surrender while living in European exile, far from his beloved homeland. After devoting his life to his cherished dream of a self-reliant white people’s republic, he died in 1904 in Switzerland, a blind and broken man.

Conclusion

Sir Alfred Milner, British High Commissioner for South Africa.

When the fighting began in October 1899, the British confidently expected their troops to victoriously conclude the conflict by Christmas. But this actually proved to be the longest, costliest, bloodiest and most humiliating war fought by Britain between 1815 and 1914. Even though the military forces mobilized in South Africa by the world’s greatest imperial power outnumbered the Boer fighters by nearly five to one, they required almost three years to completely subdue the tough pioneer people of fewer than half a million.

Britain deployed some 336,000 imperial and 83,000 colonial troops — or 448,000 altogether. Of this force, 22,000 found a grave in South Africa, 14,000 of them succumbing to sickness. For their part, the two Boer republics were able to mobilize 87,360 fighters, a force that included 2,120 foreign volunteers and 13,300 Boer-related Afrikaners from the British-ruled Cape and Natal provinces. In addition to the more than 7,000 Boer fighters who lost their lives, some 28,000 Boers perished in the British concentration camps — nearly all of them women and children.

note 46

The war’s non-human costs were similarly appalling. As part of Kitchener’s “scorched-earth” campaign, British troops wrought terrible destruction throughout the rural Boer areas, especially in the Orange Free State. Outside of the largest towns, hardly a building was left intact. Perhaps a tenth of the prewar horses, cows and other farm stock remained. In much of the Boer lands, no crops had been sown for two years.

note 47

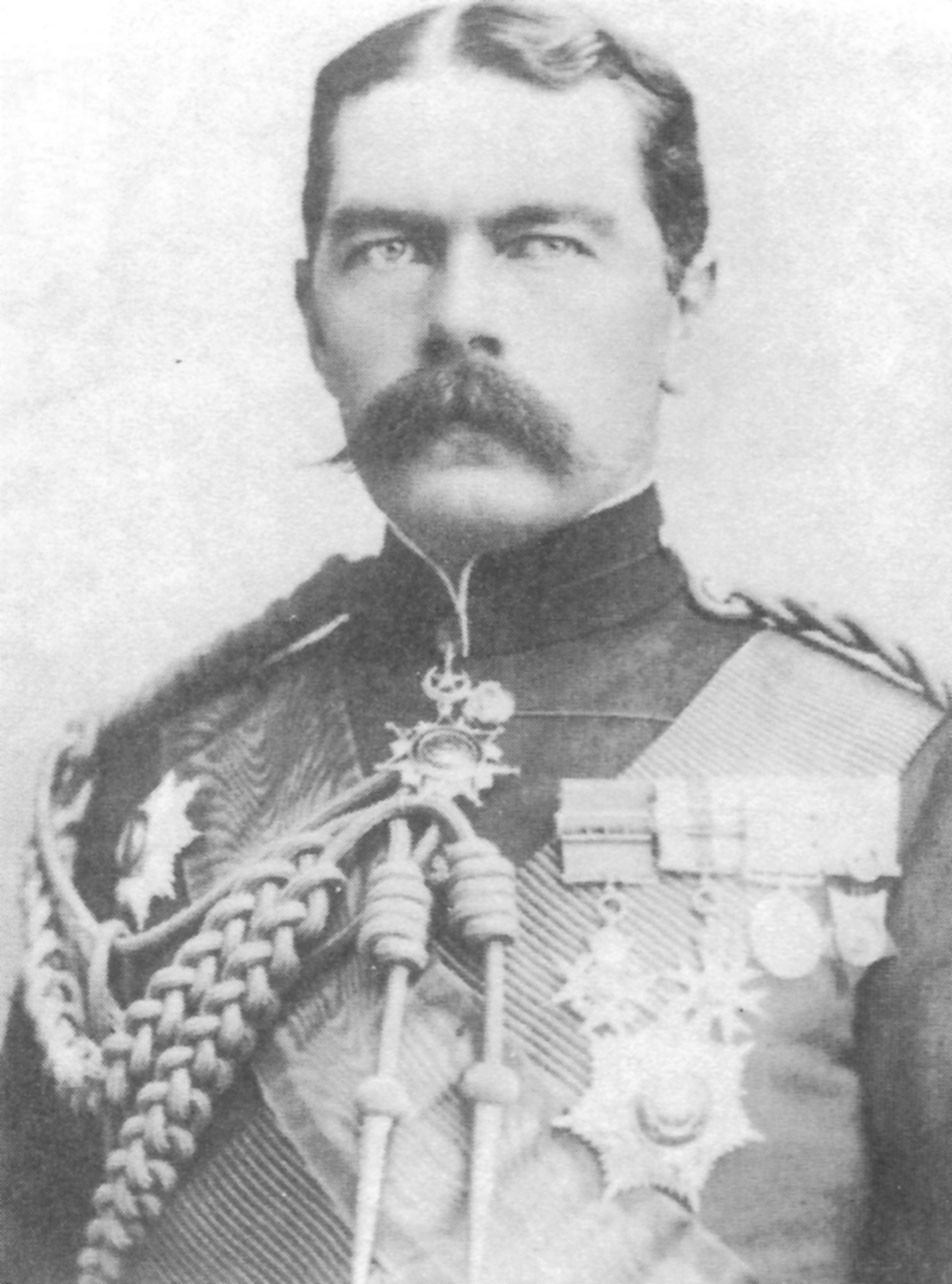

Even by the standards of the time (and certainly by those of today), British political and military leaders committed frightful war crimes and crimes against humanity against the Boers of South Africa — crimes for which no one was ever brought to account. General Kitchener, for one, was never punished for introducing measures that even a future prime minister called “methods of barbarism.” To the contrary, after concluding his South African service he was named a viscount and a field marshal, and then, at the outbreak of the First World War, was appointed Secretary of War. Upon his death in 1916, he was remembered not as a criminal, but rather idolized as a personification of British virtue and rectitude.

note

48

In a sense, the Anglo-Boer conflict was less a war between combatants than a military campaign against civilians. The number of Boer women and children who perished in the concentration camps was four times as large as the number of Boer fighting men who died (of all causes) during the war. In fact, more children under the age of 16 perished in the British camps than men were killed in action on both sides.

The boundless greed of the Jewish “gold bugs” coincided with the imperialistic aims of British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, the dreams of gold and diamond baron Cecil Rhodes, and the political ambitions of Alfred Milner. On the altar of their avarice and ambition, they sacrificed the lives of some 30,000 people who wanted only to live in freedom, as well as 22,000 young men of Britain and her dominions.

At its core, Britain’s leaders were willing to sacrifice the lives of many of her own sons, and to kill men, women and children in a far-away continent, to add to the wealth and power of an already immensely wealthy and powerful worldwide empire. Few wars during the past one hundred years were as avoidable, or as patently crass in motivation as was the South African War of 1899-1902.

Notes

1. M. Davitt,

The Boer Fight For Freedom, p. 425. See also: A. Thomas,

Rhodes, pp. 143-144; F. Welsh, South Africa: A Narrative History, p. 303; “Kruger, Stephanus Johannes Paulus,” Encyclopaedia Britannica (Chicago), 1957 edition, vol. 13, pp. 506-507.

2. F. Welsh,

South Africa: A Narrative History, p. 302.

3. A. Thomas,

Rhodes, pp. 172-181; Reader’s Digest Association,

Illustrated History of South Africa, p. 174; See also S. Kanfer,

The Last Empire, esp. pp. 96, 101-111.

4. See S. Kanfer,

The Last Empire.

5. J. Flint,

Cecil Rhodes, pp. 86-93. See also: P. Emden,

Randlords (1935).

6. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, pp. 86-87.

7. G. Saron and L. Hotz, eds.,

The Jews in South Africa, pp. 193-194.

8.

Report of the Select Committee of the Cape of Good Hope House of Assembly on the Jameson Raid (1897), pp. 165, 167.

9. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, pp. xxv, 87, 121; A. Thomas,

Rhodes, p. 284.

10. A. Thomas,

Rhodes, pp. 284-304; S. Kanfer,

The Last Empire, pp. 129-131; Chamberlain’s speech of Nov. 11, 1895, is also quoted in: Robin W. Winks, ed.,

British Imperialism (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967), p. 80.

11. G. Saron & L. Hotz, eds.,

The Jews in South Africa (1955), pp. 193-194;

Second Report from the Select Committee on British South Africa (1897), p. vii.

12. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, p. 1. Also quoted in: A. Thomas,

Rhodes, p. 337.

13. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, p. 88.

14. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, p. 518.

15. T. Pakenham,

Scramble, p. 558.

16. Claire Hirshfield, “The Boer War and the Issue of Jewish Responsibility” (1978), p. 4.

17. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, pp. 90-92, 103, 104, 107.

18. P. Knightley,

The First Casualty (1976), pp. 77-78.

19. Quoted in: Phillip Knightley,

The First Casualty, p. 75.

20. W. Ziegler, ed.,

Ein Dokumentenwerk Über die Englische Humanität (1940), p. 199.

21. Reader’s Digest Association,

Illustrated History of South Africa, p. 246.

22. Reader’s Digest Association,

Illustrated History of South Africa, p. 246.

23. During the American Civil War, Union forces rounded up large numbers of civilians who were considered hostile to Federal authority and interned them in “posts.” President Truman’s grandmother, with six of her children, was held in one such “post,” which Truman said was really a “concentration camp.” Source: Merle Miller,

Plain Speaking: An Oral Biography of Harry S. Truman (New York: 1974), pp. 78-79. See also: M. Weber “The Civil War Concentration Camps,”

The Journal of Historical Review, Summer 1981, p. 143. In September 1918, the fledgling Soviet government issued a decree that ordered: “It is essential to protect the Soviet Republic from class enemies by isolating them in concentration camps.” Sources: D. Volkogonov,

Lenin: A New Biography (New York: 1994), p. 234; M. Heller & A. Nekrich,

Utopia in Power (New York: 1986), p. 66.

24. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, pp. 533-539; T. Pakenham, Scramble, pp. 578; A rather detailed report by Hobhouse about the camps is in: S. Koss,

The Pro-Boers, pp. 198-207.

25. P. Knightley,

The First Casualty, pp. 75-76. Source cited: UK Public Record Office, W.O. 32/8061.

26. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, pp. 607; T. Pakenham,

Scramble, pp. 578-579; Reader’s Digest Association,

Illustrated History of South Africa, p. 256.

27. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, p. 534, 540-541; S. Koss,

The Pro-Boers, pp. 216, 238.

28. S. Koss,

The Pro-Boers, pp. 238-239 (note)

29. P. Knightley,

The First Casualty, p. 72; T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, pp. 539-540.

30. In a speech on Nov. 27, 1899, Lloyd George said that the Uitlanders on whose behalf Britain had presumably gone to war were German Jews. Right or wrong, the Boers were better than the people Britain was defending in South Africa. And in a speech on July 25, 1900, Lloyd George said: “… A war of annexation, however, against a proud people must be a war of extermination, and that is unfortunately what it seems we are committing ourselves to — burning homesteads and turning women and children out of their homes.” Source: Bentley Brinkerhoff Gilbert,

David Lloyd George: A Political Life (Ohio State Univ. Press, 1987), pp. 183, 191.

31. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, pp. 547-548.

32. P. Knightley,

The First Casualty, pp. 72, 73, 75.

33. Byron Farwell, “Taking Sides in the Boer War,”

American Heritage, April 1976, pp. 22, 24, 25.

34. Speech of October 18, 1899. S. Koss,

The Pro-Boers, p. 43.

35. C. Hirshfield, “The Boer War and the Issue of Jewish Responsibility” (1978), pp. 5, 15; Robert S. Wistrich,

Antisemitism (1992), p. 105-106, p. 281 (n. 10, 11). Source cited: C. Hirshfield, “The British Left and the ‘Jewish Conspiracy’,”

Jewish Social Studies, Spring 1981, pp. 105-107.

36. C. Hirshfield, “The Boer War and the Issue of Jewish Responsibility,” pp. 11, 20; Also quoted in: Robert S. Wistrich,

Antisemitism (1992), p. 281 (n. 11). Source cited: C. Hirshfield, “The British Left and the ‘Jewish Conspiracy’,”

Jewish Social Studies, Spring 1981, pp. 106-107.

37. C. Hirshfield, “The Boer War and the Issue of Jewish Responsibility,” pp. 10, 20. Burns’ speech of Feb. 6, 1990, is also quoted in part in S. Koss,

The Pro-Boers, pp. 94-95. It is also quoted (although not entirely accurately) in: R. S. Wistrich,

Antisemitism (1992), p. 281 (n. 11). Source cited: C. Hirshfield, “The British Left and the ‘Jewish Conspiracy’,”

Jewish Social Studies, Spring 1981, p. 105.

38. C. Hirshfield, “The Boer War and the Issue of Jewish Responsibility,” pp. 10, 20.

39. An excerpt of Davitt’s speech of October 17, 1899, is given in: S. Koss,

The Pro-Boers, pp. 33-34. Davitt also wrote a book,

The Boer Fight For Freedom, published in 1902.

40. Hobson is perhaps best known as the author of

Imperialism: A Study, a classic treatise on the subject first published in 1902.

41. C. Hirshfield, “The Boer War and the Issue of Jewish Responsibility,” pp. 13, 23; J. A. Hobson,

The War in South Africa: Its Causes and Effects (1900 and 1969), p. 189.

42. J. A. Hobson, “Johannesburg Today,”

Manchester Guardian, Sept. 28, 1899. Reprinted in: S. Koss,

The Pro-Boers, pp. 26-27.

43. J. A. Hobson,

The War in South Africa, p. 197.

44. C. Hirshfield, “The Boer War and the Issue of Jewish Responsibility,” pp. 13, 23.

45. S. Koss,

The Pro-Boers, p. 54.

46. T. Pakenham,

The Boer War, pp. 607-608; T. Pakenham,

Scramble, p. 581.

47. F. Welsh,

South Africa: A Narrative History (1999), p. 343.

48. In his honor, the city of Berlin in Ontario province, Canada, was renamed Kitchener in 1916, a move that reflected the anti-German hysteria of the day.

Bibliography

Barbary, James.

The Boer War. New York: 1969.

Davitt, Michael.

The Boer Fight For Freedom. New York: 1902 and 1972.

Emden, Paul.

Randlords, London: 1935.

Farwell, Byron.

The Great Anglo-Boer War. New York & London: 1976.

Farwell, Byron. “Taking Sides in the Boer War,”

American Heritage, April 1976, pp. 20-25, 92-97.

Flint, John.

Cecil Rhodes. Boston: 1974.

Hirshfield, Claire. “The Boer War and the Issue of Jewish Responsibility.” Pennsylvania State University, Ogontz Campus, 1978. Unpublished manuscript, provided by the author. A revised version was scheduled for 1980 publication in

The Journal of Contemporary History. A version of this paper was published in the Spring 1981 issue of

Jewish Social Studies under the title “The British Left and the ‘Jewish Conspiracy’: A Case Study of Modern Anti-Semitism.”

Hobson, John A.

The War in South Africa: Its Causes and Effects. New York: 1900 and 1969.

Kanfer, Stefan.

The Last Empire: De Beers, Diamonds and the World. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1993.

Knightley, Phillip.

The First Casualty. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976.

Koss, Stephen.

The Pro-Boers: The Anatomy of an Antiwar Movement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973.

Reader’s Digest Association [Dougie Oakes, ed.].

Illustrated History of South Africa: The Real Story. Pleasantville, New York: Reader’s Digest, 1988.

Ogden, J. J.

The War Against the Dutch Republics in South Africa: Its Origin, Progress and Results. Manchester: 1901.

Pakenham, Thomas.

The Boer War. New York: Random House, 1979.

Pakenham, Thomas.

The Scramble for Africa. New York: Random House, 1991.

Report of the Select Committee of the Cape of Good Hope House of Assembly on the Jameson Raid. London: 1897.

Rhoodie, Denys O.

Conspirators in Conflict. Capetown: 1967.

Saron, Gustav and Louis Hotz, eds.

The Jews in South Africa. Oxford: 1955.

Second Report from the Select Committee on British South Africa. London: 1897.

Spies, S. B.

Methods of Barbarism?: Roberts and Kitchener and Civilians in the Boer Republics. Cape Town: 1977.

Thomas, Anthony.

Rhodes: The Race for Africa. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Welsh, Frank.

South Africa: A Narrative History. New York: Kondansha, 1999.

Wistrich, Robert S.

Antisemitism: The Longest Hatred. New York: Pantheon, 1992.

Ziegler, Wilhelm, ed.,

Ein Dokumentenwerk Über die Englische Humanität. Berlin, 1940.

From

The Journal of Historical Review, May-June 1999 (Vol. 18, No. 3), pages 14-27. This essay is a revision and expansion of an essay that was first published in the Fall 1980 issue of

The Journal of Historical Review.